The Kitchens I Can’t Return To

A mostly photographic reflection on home and family in Burkina Faso

I’ve been meaning to write a post about kitchens in Burkina Faso for a while. Burkina Faso, a landlocked country in West Africa, is the place where I did my PhD research in social anthropology, focusing on the social meaning of food in everyday life in the town of Bobo-Dioulasso, which included poking my nose in people’s kitchens and pots.

The name “Burkina Faso” means “the land of upright people” or “the land of people with integrity” — a name that speaks to the values so many Burkinabè live by. From my first visit in 1997 to my last in March 2020, I’ve probably travelled there more than 40 times and spent over 60 months in total, which adds up to about five years of my life. I have close friends there, and people I consider my adoptive family: a mother, sisters and brothers, children, even grandchildren. It is a place know well, I speak one of the local languages and have visited nearly every region and province in the country.

Over the years, while in Burkina (as it is commonly referred to), I’ve had several close brushes with death: a severe case of hepatitis, malaria, and a major terrorist attack. I have enough material to write not one, but several memoirs. And yet, I struggle to put anything in writing.

There are a number of reasons why I find it hard to write about this. One of them is the fact that I’m a white woman. These days, being white and writing about Africa comes with more responsibility (and rightly so) than it did in the past, when white privilege — especially in writing about places once referred to as the Third World — was rarely questioned.

And yet, that’s not really what’s stopping me. The deeper reason is the grief I carry for Burkina.

When I was last in the country, during a brief visit to the capital Ouagadougou, in March 2020, just as the pandemic began, I had no idea it would be my final visit for more than five years. I didn’t expect to be kept away by the pandemic (I was one of those people who thought it would last two weeks), and I certainly didn’t imagine that the country I considered my second home —where I had once hoped to build a house, plant trees, maybe even retire — would become so troubled that most Western governments now advise against travel. Over 40% of the country is under the control of violent extremist organisations1.

My Burkinabè mother is elderly, and there’s no telling how long she will live. And still, I don’t feel I can just get on a plane and go.

A few Europeans I know did visit in February and March, the time of the wonderful biannual Pan-African film festival, FESPACO, which I had the chance to attend five or six times between 1999 and 2015. But the most recent information I’ve received from people studying the region is that it’s simply not safe — especially for someone like me. I would stand out as a white woman, and given my PTSD from a past terrorist attack, the idea of traveling across the country to Bobo-Dioulasso, where my adoptive family and many friends live, feels too risky.

Others may be braver, but I don’t have that kind of courage right now. And that makes it harder to write about the life I once had there.

Recently, a Portuguese friend, an art and photography teacher, asked me to give a presentation about everyday life in Burkina Faso for her photography students here in Lisbon. It’s an interactive class: I’ll share stories and images from my work, and the students will use them to inspire their own creative assignments through photography and collage.

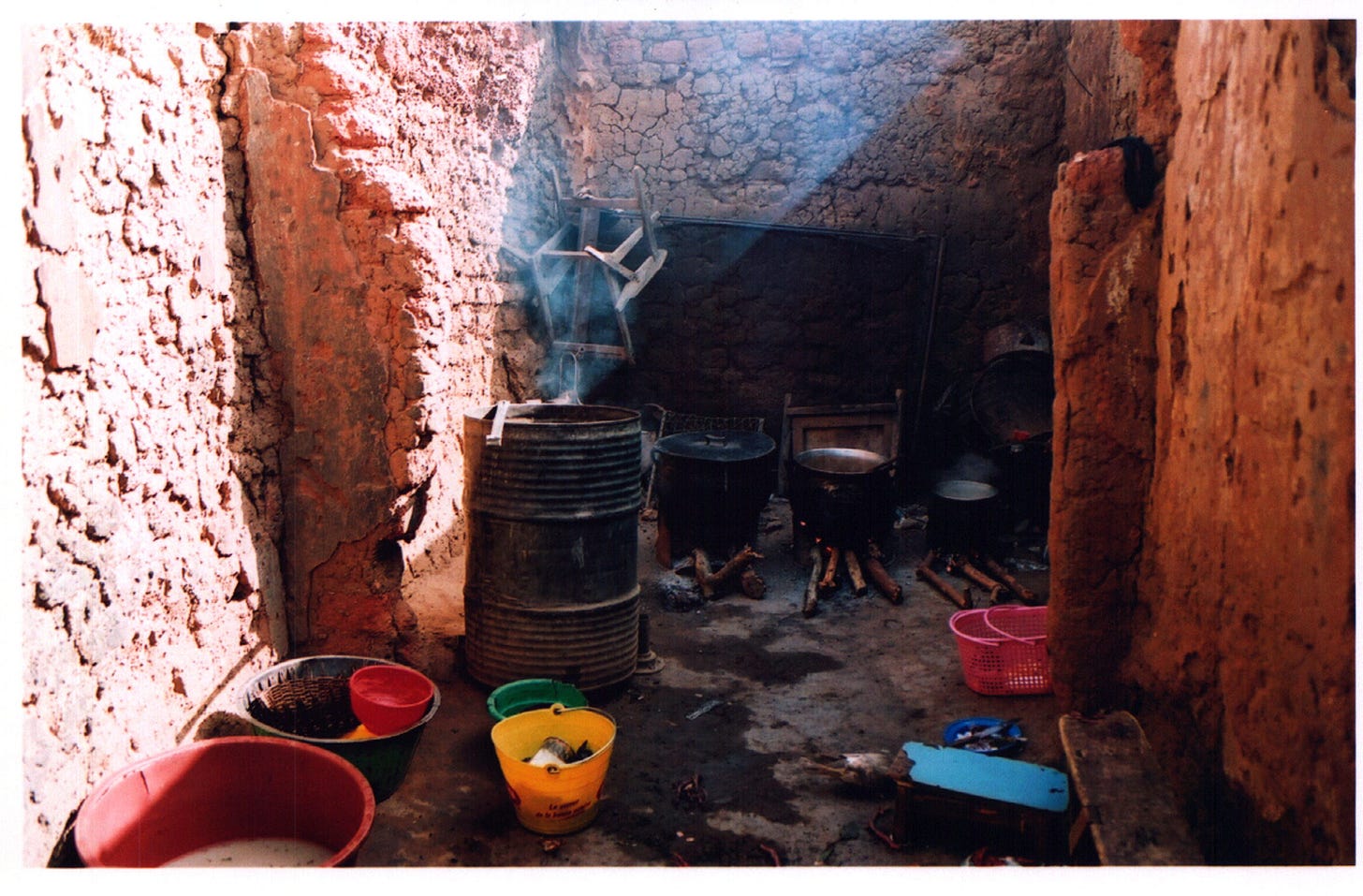

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been going through 20 years of photo archives from Burkina: images from my African family’s compound, of women and girls cooking, of the kitchens I observed in Bobo-Dioulasso during my PhD fieldwork.

I’m not quite ready to write about all of this. But I’ve decided to share a few of these photos here, as an homage to the beautiful people of Burkina Faso — people I miss deeply, in a way that’s hard to put into words.

I hope you, too, can see the beauty of these kitchens and the women who cook in them.

https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel

Ten years ago, I worked as Assistant Editor and Associate Producer on the documentary Sembene! about the filmmaker who founded FESPACO, Ousmane Sembene. Sankara, was one of Sembene’s personal heroes. I watched so much footage shot in Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso that I feel strangely at home looking at your photos. I can also understand your despair at being parted from this part of the world that engenders such deep emotion. You can rent the doc Sembene! on Apple TV+ if you want to feel less homesick. Also, his last film, Moolaadé, was filmed in a very remote, very beautiful village in Mali - you can find it on the Criterion channel. Jërëjëf for the post.

I felt sad reading this, knowing it’s too dangerous for you to visit when it’s so obvious your heart is very much there. The photos are are beautiful. I hope you can go back one day. Can you communicate with your adoptive mother and sisters or is it complicated?